Alex Kinney follows the sociological studies of cannabis from the early 1900s to the present day, and highlights some of what may lie ahead.

The following is an article produced by a contributing author. Growers Network does not endorse nor evaluate the claims of our contributors, nor do they influence our editorial process. We thank our contributors for their time and effort so we can continue our exclusive Growers Spotlight service.

Cannabis Sociology

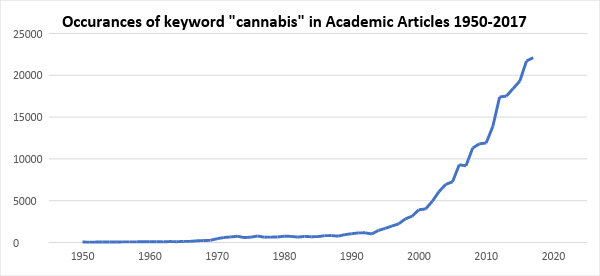

The dramatic shift in recent years in the regulation and accessibility of cannabis for consumers has unsurprisingly created a monumental pivot in thought surrounding the plant once considered a central antagonist or “public enemy number one” in Nixon’s “War on Drugs”.1 Unsurprisingly, academics have followed suit, paying increasingly more attention to the role of cannabis in medical, botanical, and social life. Since 1996 when cannabis was legalized for medical use in California, the presence of cannabis as a term in academic articles has spiked over ten-fold from 1970 occurrences to a whopping 22,100 occurrences in 2017. Figure 1 below demonstrates this change. This begs the question, what in the world have we been talking about?

Though I don’t presume to be an expert on all things scholarly, the field of sociology has a rich tradition of incorporating cannabis studies into our repertoire. A brief search of the popular online library JSTOR shows that sociologists have published 2608 articles on cannabis since 1929. The purpose of this article article is to serve as an introduction to the sociology of cannabis. Over the next few passages, I will outline what has been explored in sociological research regarding cannabis including the types of impacts this research has had both in the way we think about cannabis and policy, and some new directions that should be undertaken in future research.

The Foundations of the Sociology of Cannabis: 1920-2000

The first article that charted the social life of cannabis was an assessment commissioned by the Bombay government to assess the variable differences between cannabis farming practices present in then-colonized India and the West. Mann (1929) described a “peasant” industry where the production of jute — a natural fiber similar to cotton — was concentrated on monopolized farms, leaving the rest of the country to cultivate the production of cheaper, Deccan hemp (Hibisicus cannibus). He later noted that “true hemp (Cannabis indica), though common in many parts of the country, was never grown for fibre, but was cultivated for the intoxicating drug known as hashish or ganja,” codifying an academic division that would persist between industrial cannabis as a capital market as opposed to its use as a personal vice.

This distinction is important primarily because the bulk of sociological research to date has focused on the consumption of cannabis as opposed to its production. Early titles focusing in on the social influences of cannabis were concerned with impacts on racialized harmony, (2)(3) use of narcotics and psychopathy,4 and “bohemian” culture characterized by “various circles of perversion” including “marihuana, homosexual, hard drinking, or sex-obsessed rings” that were ensnaring the irresponsible youth.5 This unflattering portrayal of cannabis as a social problem mirrored public fervor surrounding children who were swept up in reefer madness, setting the tone for public policy on cannabis for the decades following the 1930s.

This trend continues until the 1950s when Howard Becker – still considered canonical for introductory sociology students – introduced a fresh, empirical take on cannabis as a socialization process. Becker’s (1953) Becoming a Marihuana User critically outlined that cannabis use was not pathological and deviant, but rather “a sequence of social experiences during which the person acquires a conception of the meaning of the behavior, and perceptions and judgements of objects and situations, all of which make the activity possible and desirable”. Becker posited an at-the-time-provocative thesis that cannabis was not addictive. After an interview study of fifty cannabis users, he asserted that in order to become a routine consumer, cannabis users must:

- Learn how to appropriately consume cannabis.

- Recognize the effects of cannabis intoxication.

- Come to find the effects to be desirable.

This stark contrast from prior treatments of cannabis attempted to transition the rhetoric of cannabis towards acknowledgment that consuming cannabis represents a unique social practice, relying upon learned behavior that can be enjoyable.

Still, cannabis continued to harbor a not-so-savory reputation as an object of study for sociologists throughout the 1960s. Research primarily focused on the relationship that cannabis had as a deviant act. Deviance studies during this period were at an apex of popularity, given the groundswell of activism, social justice initiatives, and moral transitions occurring as a result of the countercultural shift in the United States.(6)(7)(8) Cannabis was often lumped into other narcotic studies seeking to make generalized propositions about drug culture.(9)(10)(11) As a result, it is not a far stretch to claim that the sociology of cannabis primarily found its roots in a conservative backlash against the moral panic surrounding the countercultural youth.

Sociological research in the 1970s and 1980s mirrored this trend as cannabis ultimately became institutionalized as a Schedule 1 substance following the passage of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. During this period, the criminal justice implications of cannabis use and legal ramifications of cannabis policy came to supplant the consumption of cannabis as the primary object of inquiry in sociology.(12)(13)(14) However, an important and understated shift occurred during this period as, for the first time, sociology began to question the roots of cannabis law. The critical turn in the discipline prompted scholars to start questioning the origins and consequences of unequal applications and frameworks of cannabis policy. (15)(16)(17)(18) Sociologists noticed that cannabis was and is a widespread social token that could highlight differential treatment of race, class, and gender in the criminal justice system. To this end, research shifted subtly towards a recognition on how cannabis had different impacts on different groups of people.

Though it might be arbitrary to signal that the “contemporary” period of research began in the 1990s, data shows that academic interest in cannabis exploded during this period across disciplines. More academic articles were published during this decade alone (17,700) than from 1950-1990 combined (16121). The explosion in research correlated to the relaxing of cultural attitudes surrounding cannabis. This relaxation in attitudes led to not only a rise in policy shifts leading to the development of the medical cannabis industry, but also increased access to cannabis and cannabis populations for researchers.

For sociologists, there was a considerable lag during this transition. Cannabis continued to be included as a variable in studies assessing crime risks and drug dependence. Given that the 1990s were (for traditionally advantaged people) a fruitful economic period, sociologists were transitioning away from critical approaches towards the economy as a unit of analysis.19

A few important studies worked to counteract longstanding political myths surrounding cannabis. Register and Williams (1992) took aim at cannabis stereotypes, provocatively arguing that cannabis use actually increased labor market productivity across a sample of youth. Sociologists began to envision what the economic windfall would look like from a fully regulated cannabis market,20 and notably, got some things wrong arguing that cannabis decriminalization was a “fragile, brief, and limited” reform movement.21 Only two years later California would enact Proposition 215 that legalized access to cannabis for medical patients.

New Directions in the Sociology of Cannabis

As regulations firmly shifted in the 2000s and into the 2010s, cannabis has become a multifaceted social construct. But, as Pederson (2009:135) notes, “surprisingly few researchers from sociology or other social science disciplines have investigated cannabis use in recent years.” In the following section, I’ll detail some potential new directions given this critical lapse in attention to one of the oldest and fastest-growing markets.

Distilling the Plurality of Cannabis: The Sociology of Cannabis as a Multiple Plant

A persistent feature in sociological cannabis studies was the effort to consider cannabis as a singular, unified object for human consumption. Current research questions this outdated conception of cannabis, and should prompt us to investigate cannabis as a multiple or plural plant. Pioneering work by Rowland and Spaniol (2015:556) pushed us away from thinking of objects as singular, towards the “multiplicity [of] objects that seem singular, but when they are observed in practice, they appear to multiply.” In other words, we can think of cannabis as a singular plant, but at the same time investigate the meaning and consequences of cannabis based on its multiple utilities, social facets, and its unequal impacts on various social groups.

The new sociology of cannabis should open more interdisciplinary advancements in research that conceptualizes the cannabis plant as the sum of its parts. For example, the rise of CBD-based treatments for medical relief can hardly be partitioned into the same category of use as recreational THC consumption. This type of framework may challenge or expand upon longstanding foundations in the sociology of cannabis such as the process of socialization outlined by Becker in 1953.

As a result, this framework begs for more sensitivity from sociologists to distill the accurate social nature of cannabis consumption, lest we make erroneous conclusions that produce erroneous science and/or harm the general population through bad policy. In some ways, this framework draws on the foundational work of Mann (1929) who importantly distinguished the different agricultural impacts of cultivating hemp as opposed to its intoxicating uses. New directions in the sociology of cannabis should be open to embracing medical, botanical, biological, and chemical advancements in cannabis research to design studies assessing both the similarities and differences in cannabis use in light of our changing understanding of cannabis as a multifaceted substance.

Institutional Impacts of Cannabis: Regulations, Policies, and Markets

While scholars have flirted with the relationship between cannabis and institutional processes, social scientists (and in particular sociologists and economists) have failed to explicitly examine how the exploding commercial industry is impacting political, cultural, and economic institutions. Despite the foundational work that is setting sociologists up to view cannabis as more than a strawman for deviance studies, we have yet to transition towards embracing the commercial cannabis industry as a unique opportunity to explore just exactly how moral goods become embraced and legitimized in society.

This is not to say that cannabis has achieved a perfectly stellar reputation in the eyes of the general public; rather, after decades of unpopularity, it is clear that we are in the midst of a shift towards international policy reform reflecting changes in the cultural sentiment towards cannabis.22 This asks the question of what the long-term impacts of this shift will have on not just cannabis as a social practice, but also on broader regulations, policies, and markets that will be increasingly intertwined with the cannabis industry.

Theoretically, institutional studies would benefit from a greater understanding of how contradictory and confusing institutions influence industrial and agricultural regulations, norms, and routines. For example, how does the industry remain viable when there are conflicts between different laws guiding each respective state marketplace, between the state and federal levels where cannabis is simultaneously sanctioned and criminalized, and even between international law where certain countries such as Canada embrace national reform with bordering countries that remain obstinate towards regulatory change? Answering questions such as these will have critical impacts on academic theory about how institutions change and whether they are as stable and enduring as we have though for most of scholarly history.23

At the policy level, answering these questions should also provide governing bodies the opportunity to see what works and what doesn’t when they are pressured to change their stance on longstanding but flawed policy. While our research is often purposefully or accidentally overlooked by the people that make policy,20 this does not mean that systematic policy recommendations should not be given on the grounds that sociologists are uniquely equipped to answer the how and why questions that follow when an industry such as cannabis forcefully changes its status in society.

References

- Avilés, William. 2017. The Drug War in Latin America: Hegemony and Global Capitalism. Routledge.

- Becker, Howard S. 1953. “Becoming a Marihuana User.” American Journal of Sociology 59(3):235–42.

- Bourque, Andre. 2018. “Researchers Recognize an International ‘Tide Effect’ Driving Worldwide Cannabis Reform.” Entrepreneur. Retrieved June 11, 2018 (https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/307101).

- Caputo, Michael R. and Brian J. Ostrom. 1994. “Potential Tax Revenue from a Regulated Marijuana Market: A Meaningful Revenue Source.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 53(4):475–90.

- Carey, James T. and Jerry Mandel. 1968. “A San Francisco Bay Area ‘Speed’ Scene.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 9(2):164–74.

- Cohen, Albert K. 1965. “The Sociology of the Deviant Act: Anomie Theory and Beyond.” American Sociological Review 30(1):5–14.

- Davis, Fred and Laura Munoz. 1968. “Heads and Freaks: Patterns and Meanings of Drug Use Among Hippies.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 9(2):156–64.

- Galliher, John F., James L. McCartney, and Barbara E. Baum. 1974. “Nebraska’s Marijuana Law: A Case of Unexpected Legislative Innovation.” Law & Society Review 8(3):441–55.

- Grupp, Stanley. 1967. “EXPERIENCES WITH MARIHUANA IN A SAMPLE OF DRUG USERS.” Sociological Focus 1(2):39–51.

- Grupp, Stanley E. and Warren C. Lucas. 1970. “The ‘Marihuana Muddle’ as Reflected in California Arrest Statistics and Dispositions.” Law & Society Review 5(2):251–69.

- Guillen, Maruo F., Randall Collins, and Paula England. 2005. The New Economic Sociology: Developments in an Emerging Field. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Johnson, Weldon T., Robert E. Petersen, and L. Edward Wells. 1977. “Arrest Probabilities for Marijuana Users as Indicators of Selective Law Enforcement.” American Journal of Sociology 83(3):681–99.

- KOSKI, PATRICIA R. and DOUGLAS LEE ECKBERG. 1983. “Bureaucratic Legitimation: Marihuana and the Drug Enforcement Administration.” Sociological Focus 16(4):255–73.

- Mann, H. H. 1929. “The Agriculture of India.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 145(2):72–81.

- Redfield, Robert. 1929. “The Antecedents of Mexican Immigration to the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 35(3):433–38.

- Register, Charles A. and Donald R. Williams. 1992. “Labor Market Effects of Marijuana and Cocaine Use among Young Men.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 45(3):435–48.

- Reuter, Peter. 1986. “Risks and Prices: An Economic Analysis of Drug Enforcement.” Crime and Justice 7:289–340.

- Rowland, Nicholas J. and Matthew J. Spaniol. 2015. “The Future Multiple.” Foresight 17(6):556–73.

- Scott, W. Richard. 2010. “Reflections: The Past and Future of Research on Institutions and Institutional Change.” Journal of Change Management 10(1):5–21.

- Shaw, Claire. 2015. “Unloved and Sidelined: Why Are Social Sciences Neglected by Politicians?” The Guardian, March 11.

- Simmons, J. L. 1965. “Public Stereotypes of Deviants.” Social Problems 13(2):223–32.

- Snyderman, George S. and William Josephs. 1939. “Bohemia: The Underworld of Art.” Social Forces 18(2):187–99.

- Volker Strobel. 2018. Pold87/Academic-Keyword-Occurrence: First Release. Zenodo.

10 Best Gift Ideas for Cannabis Connoisseurs and Growing Aficionados (2022)

December 7, 2022Developing and Optimizing a Cannabis Cultivation System

December 14, 2021Dealing with Insomnia: How Can CBD Help?

December 10, 2020Your Guide to Sleep and CBD

December 7, 2020

Do you want to receive the next Grower's Spotlight as soon as it's available? Sign up below!

Resources:

Want to get in touch with Alex Kinney? He can be reached via the following methods:

- Email: abk5074@email.arizona.edu

Do you have any questions or comments?

About the Author

Alexander B. Kinney is a PhD Candidate in Sociology at the University of Arizona. His interests mainly lie in advancing institutional theory by exploring the foundations of institutional change, understanding the dynamics of field transformation, and studying the diffusion of technology in emerging and extra-institutional economies. His dissertation explores how individuals in the emerging commercial cannabis industry negotiate contradictory regulations and unclear norms through the use of temporary, "provisional" institutions designed to provide both immediate support for business activities and become obsolete over time.