Editor's Note: Let us know if you'd like to see more articles like this in the survey and comments below!

If you would like to skip to any portion of this article, please click the links the below:

In the Beginning

Cannabis has a long history of use by humans all over the world. Though the plant didn’t reach the Americas until the 17th century, it has been a consistent part of the culture ever since. Opinions vary on how effective it is for use in medicinal, religious, and recreational settings, but it is indisputable how versatile the plant is and the variety of products that can be produced from it. In fact, in a 1938 a Popular Mechanics article, Cannabis was touted as a new miracle miracle crop capable of supplying the country with not only a plethora of cannabis-based products, but also new infrastructure and jobs.

Despite its versatility and benefits, Cannabis was banned early everywhere in the early 20th century and then all but forgotten in agriculture. How could this happen? Why did this happen? There are two schools of thought on this subject:

- One school of thought believes unequivocally that a few, well-connected affluent families were responsible for Cannabis prohibition

- The other school of thought dismisses that idea as a conspiracy theory and that it was just a natural societal change.

So was it a conspiracy or was it a natural societal shift? Making any kind of definitive statement would be premature, but it is likely that the truth lies somewhere in between these two extremes.

A Quick History

As we previously mentioned, Cannabis reached the Americas in the 1600s via European ships destined for South America. Already a valuable natural resource and cash crop in the Old World, its usefulness as a source of fiber, food, medicine, and fuel allowed it to take root in the New World as well. In the English colonies that would eventually become the United States, the Cannabis story began with a royal decree for hemp to be cultivated and sent back to England. The colonial farmers obliged, quickly recognizing the value of Cannabis as a cash crop, and the plant's popularity grew throughout the colonies.

The crop became a source of fiber for paper, clothing, and rope while the seeds were used for food, and the resin for lamp oil. By the 1800s the medicinal and psychotropic properties of Cannabis were well known to doctors and pharmacists, and these properties made it a popular additive to the burgeoning elixir and tonic market. This is where the story of Cannabis prohibition in the US begins.

From Unknown to Illegal

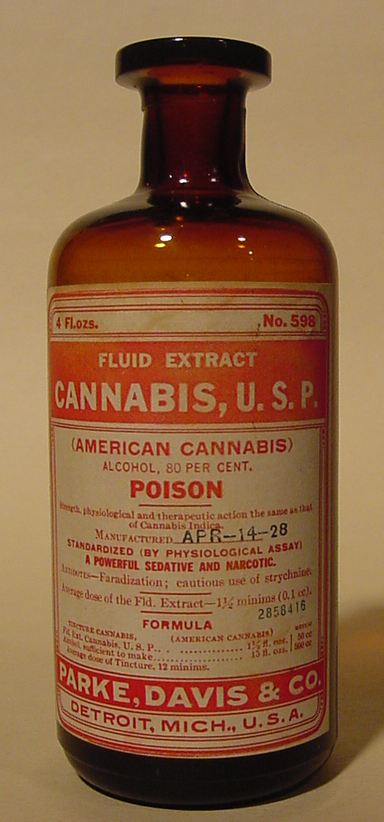

Cannabis' potential as a medical treatment was unknown to Western medicine until Irish physician William O'Shaughnessy introduced it in 1839. It caught on and by 1850 a variety of Cannabis mixtures were available as over-the-counter remedies in pharmacies everywhere, alongside other elixirs containing morphine, cocaine, and more. With no federal regulation of the market at the time, the first labeling laws were introduced in individual states. In essence, states wanted to inform consumers about what substances were in the tonics and prevent purveyors from adulterating their products. Additional laws around this time restricted the sale of Cannabis mixtures to minors, and some even required the products to be labeled as “poison” if not sold by a pharmacist.

Despite the new regulations, Cannabis remained popular medicinally and recreationally. "Hash houses" began popping up in cities across the country, with over 500 of these establishments reported in New York City alone. As the country entered the 20th century, state laws varied widely with regards to Cannabis elixir labeling.

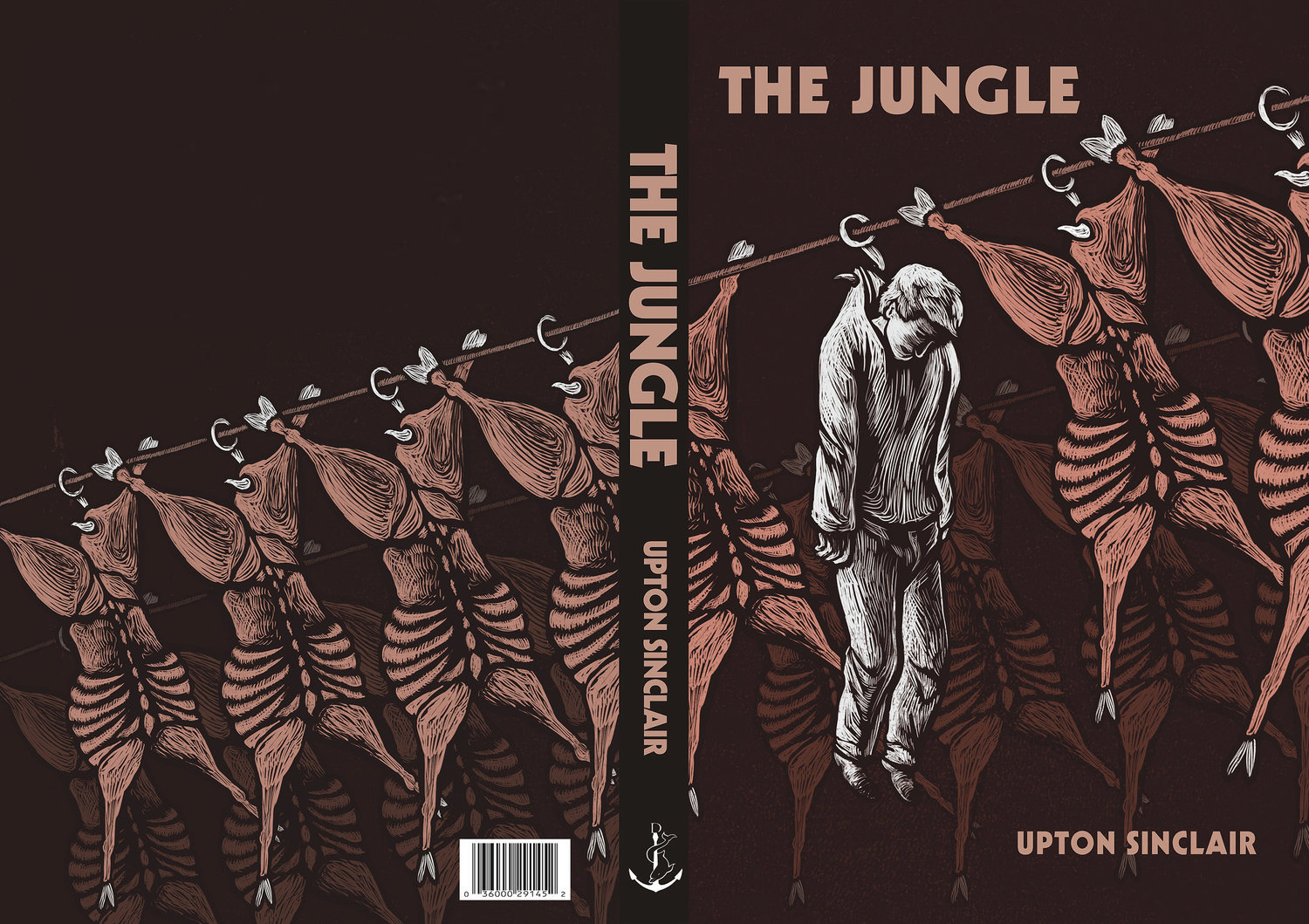

However, a book published around this time would change everything. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle is a fictional, albeit damning, indictment of the lack of sanitation and safety in the meatpacking industry in the early 20th century. The book opened eyes across the country and it served as an impetus for the first federal mandate regarding the labeling of Cannabis and other substances. In 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act was signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt.

I think we’d all agree that consumers deserve to know what’s in the products they consume, but how did an innocuous labeling law eventually become an outright Cannabis ban? The answer only begins to make sense when we ask the following: Who had the most to gain (or lose) if Cannabis caught on?

The Players

Player Number One

William Randolph Hearst was a newspaper man. His media empire in the 1920s was the biggest in the world, and was so strong that it even stands today. Hearst was heavily indebted to the Canadian timber industry because he needed their paper, and Cannabis could have potentially been a cheap alternative to timber. Given this knowledge, it would be reasonable to ask why he didn't welcome the transition to a cheaper alternative.

The likely reason is that Hearst's family owned vast timber holdings. Though a transition to Cannabis might have benefited Hearst in the short term by saving money on paper imported from Canada, what about the long term effect on his family holdings? When we couple this piece of evidence with how critical Hearst publications were of marijuana and its users, his motive to protect his assets seems plausible.

Critics of this theory may argue that many publishers were engaged in this same type of sensational reporting on marijuana. The difference is that many publishers were likely following his lead. The man wielded great power to influence public opinion, not dissimilar Rupert Murdoch in the “Fox News era.” Hearst’s own views and concerns shaped the journalism of the times. Just ask Orson Welles.

Player Number Two

The next player who had an interest in seeing Cannabis banned was chemical baron Pierre S. Du Pont (of the Du Pont family). A titan in the chemical industry, Du Pont had an interest in banning Cannabis because it would compete with his petroleum-based, polymer plastic products. However, his interest in petroleum went beyond plastics. Cannabis had potential as a fuel source, and this conflicted with Du Pont’s interests as a board member of the fledgling (and struggling) General Motors Corporation. A new term was also being thrown around in the 1920s: Chemurgy, and it scared Du Pont. Chemurgy is the concept of using agriculture to provide all of the raw materials necessary for the creation of industrial goods such food, clothing, fuel, and even cars. This would have reduced dependency on foreign imports and increased the number of jobs. Even Henry Ford was a major proponent of chemurgy. However, from Du Pont’s point of view, chemurgy was a direct threat to his petroleum products and his investments in General Motors. It's no stretch to suggest he may have felt threatened by Cannabis.

Players Three and Four

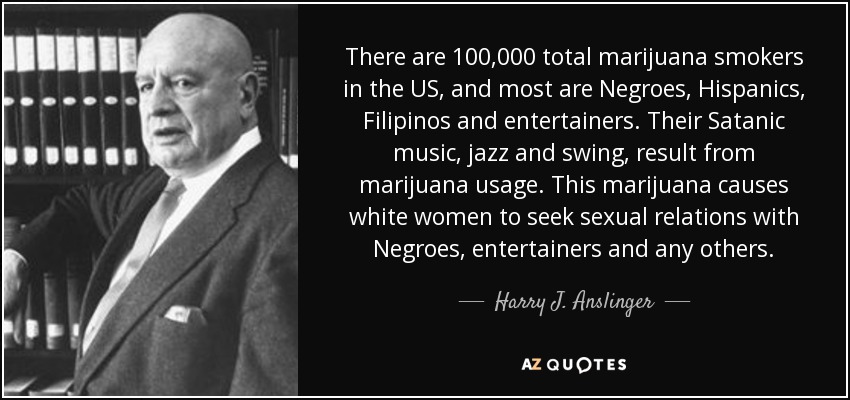

Two more people integral to the story are former Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon (the richest man in the world at the time) and ex-prohibition enforcer Harry Anslinger. From his cabinet position, Mellon (with personal ties to the oil industry and banking as well as being a financial backer of the Du Pont corporation), appointed his niece’s husband Harry Anslinger as head of the newly formed Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger was a self-made lawman, starting as a railroad police officer tasked with investigating fraud cases and later making a name for himself during alcohol prohibition. At the time of the appointment by Mellon, Anslinger was in need of a new enemy, and well-suited to head up the push against Cannabis.

So how did it play out?

A Compelling Narrative?

With Mellon's appointment of Anslinger in place to protect he and Pierre du Pont's financial interests, Hearst’s media conglomerate went to work influencing the opinion of the American public. Hearst's papers pushed horror stories about the “devil weed,” the foreign-sounding “marijuana,” and tapping into the racism of the time via reporting the “Mexicans and coloreds” were the primary users of marijuana, a media strategy of racist association proven to be employed during the Zoot Suit Riots of the 1940s. Hearst chose the Spanish term for Cannabis to intentionally to create anxiety and drum up racist fears. In fact, the term was so new to the American lexicon that most voting politicians didn’t make the connection between the word and the Cannabis they already knew. And if the most informed in society were susceptible to the ruse, what would happen when the propaganda machine was turned on the public?

With Hearst drumming up prohibition support via his media empire, Harry Anslinger’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics was given a $100,000 budget ($1.5 million when adjusted for inflation) and told to investigate. By 1937, Congress passed the "Marihuana Tax Act" (despite a protest by the American Medical Association) which levied taxes against farmers who grew Cannabis, as well as any doctors or pharmacists who purchased the plant for medicinal purposes. It’s really no wonder that the treatment was basically abandoned by doctors and pharmacists in favor of other, untaxed, pharmaceuticals such as opioids.

But Anslinger didn’t stop there. Mandatory sentence guidelines for first time Cannabis offenses were established by pushing for the Boggs Act in 1952, and by 1960, Anslinger successfully petitioned members of the UN to combine and unify all existing drug treaties into a single policy. This came to be and the result was the UN’s Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, making Cannabis cultivation, sale, possession, and use illegal nearly worldwide, with 150 countries pledging to eradicate marijuana within their borders. The trend continued domestically when President Richard Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act into law, a move that made Cannabis a schedule 1 narcotic, similar to heroin and cocaine with no recognized medical uses.

In short, an argument can be made that American xenophobia and financial uncertainty was effectively co-opted to drum up support for a Cannabis ban, essentially coupling the fear over the influx of nearly one million legal Mexican immigrants with the economic uncertainty of the USA in the 1930s. Since the Mexican laborers were known to smoke Cannabis and were employed as cheap laborers, it was easy for politicians and journalists involved to demonize the "Mexican marijuana smoker", while also promoting their own financial interests. Couple that with their financial power and political connections, and they could enact laws based on bad information, despite the objections of medical professionals who understood the plant and its medicinal value.

We haven’t even considered the social ramifications of the “War on Drugs,” such as the swelling prison population and the fact that the vast majority of these non-violent offenders are people of color. This aspect alone deserves specific attention and will be covered in a future article.

Want to know about the next contributor article as soon as it posts? Sign up with your email below.

About the Author

Chris DeWildt is a graduate of Grand Valley State University and Western Kentucky University. He worked in education and publishing for ten years before joining the team at Growers Network. In addition to editing the GN blog, Chris also works on the Canna Cribs series.