Matthew Wallenstein of Mammoth Microbes explores how microbes are the next big agricultural revolution.

The following is an article produced by a contributing author. Growers Network does not endorse nor evaluate the claims of our contributors, nor do they influence our editorial process. We thank our contributors for their time and effort so we can continue our exclusive Growers Spotlight service.

Disclaimer

This article was originally posted by Mammoth Microbes. You can read the original article here.

Walk into your typical U.S. or U.K. grocery store and feast your eyes on an amazing bounty of fresh and processed foods. In most industrialized countries, it’s hard to imagine that food production is one of the greatest challenges we will face in the coming decades.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, international initiatives referred to collectively as the Green Revolution dramatically increased food production, largely by breeding crop varieties that were able to take advantage of man-made fertilizer and developing powerful pesticides and herbicides. But as we intensified agriculture, we also intensified its environmental impacts. They include soil erosion, reduced biodiversity and the release of greenhouse gases that drive climate change.

However, we will need to almost double food production within just three decades, because by the year 2050, the human population is projected to grow from 7.5 billion to nearly 10 billion. All this production will need to happen in the face of increasing drought, herbicide and pesticide resistance, and in a world where the best cropland is already being farmed. Realistically, our ability to continuously push these systems to produce more crops year after year has largely stagnated, and is not keeping pace with rising demand. New innovations are needed to change the way we grow food and make it more sustainable.

I am part of a new crop of scientists (Editor’s Note: Pun intended) who are harnessing the power of natural microbes to improve agriculture. In recent years, genomic technology has rapidly advanced our understanding of the microbes that live on virtually every surface on Earth, including our own bodies. Just as our new understanding of the human microbiome is revolutionizing medicine and spawning a new probiotic industry, agriculture may be poised for a similar revolution.

CC BY-NC-SA

Replacing chemistry with biology: The power of microbes

In nature, plants coevolve with the microbes that live in their rooting zones (or rhizosphere), on their leaves, and even inside their cells. Plants provide microbes with food in the form of sugars, and microbes make nutrients available to the plants and help prevent disease. But as we added more and more chemicals to our fields and tilled our soils, we broke the close connection between plants and microbes by killing many of these beneficial organisms.

A few years ago, I decided to apply my expertise in soil microbes to improving agriculture. Of all things, I was actually inspired by doctors’ surprising success in using human fecal transplants to cure a chronic and often deadly bacterial infection called Clostridium difficile. By simply transplanting the fecal microbiome from a healthy person, the disease was cured, permanently! Could the same approach work in agriculture?

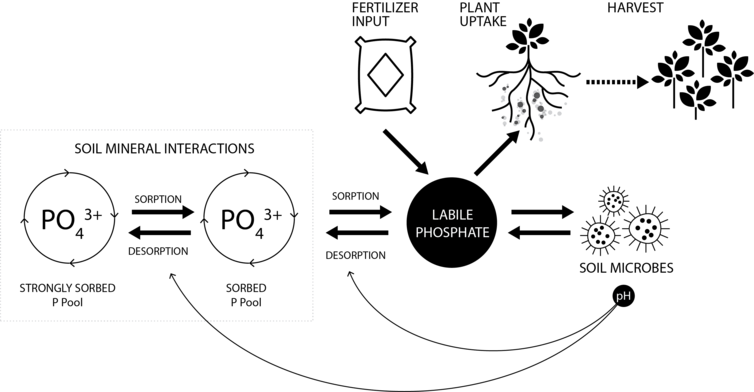

Along with my close collaborator at Colorado State University, Dr. Colin Bell, I set out to develop a microbial technology that increased the availability of phosphorus, a critical nutrient that plants need to grow. Farmers typically provide phosphorus to plants by applying fertilizer. But, when it is added to soils this way, up to 70 percent of it becomes bound to soil particles that plants can’t access.

Microbes can unlock phosphorus and other micronutrients from these particles so that plants can use them. We developed a combination of four bacteria that are exceptionally good at making phosphorus available to plants, leading to bigger, healthier plants. They do this by releasing specialized molecules that break the bonds between phosphorus and soil particles. To get this technology into the hands of farmers who can use it, we launched a startup company called Growcentia and started selling our first product, which is called Mammoth P. Mammoth P, which is a microbial product, increases plant growth by releasing phosphorus, an important nutrient, from soil particles so that plants can take it up and use it.

I’m not alone in thinking that microbes can help feed the world. Many other startups are working on microbial technologies for food production, including AgBiome, Indigo, Maronne BioInnovations, and New Leaf Symbiotics.

The world’s biggest agriculture companies are also investing heavily in biological solutions. For example, Monsanto recently invested USD $300 million in an alliance with the biotechnology company NovoZymes. Why is Big Ag getting into microbes? These companies recognize the problems caused by chemical-based agriculture and want to be part of the future. Clearly, they see the potential to make money by giving farmers new tools to produce food more efficiently and with less impact on our planet.

Growcentia focuses on soil microbes that increase nutrient efficiency and uptake, but microbes can also enhance agriculture in many other ways. Some companies are focused on commercializing microbes that have been shown to suppress plant responses to drought, which ironically tricks them into continuing to grow through dry conditions. Other companies are developing microbial products that protect plants from disease and pests. Microbes can even influence the timing of flowering. The possibilities are endless.

Scaling up

Beneficial microbes have long been used in agriculture. For decades, farmers have been adding nitrogen-fixing bacteria and symbiotic fungi called mycorrhizae to their legumes in order to help plants acquire nutrients. But many older products contain undefined mixtures of microbes and make broad claims about how they enhance plant growth. They’ve largely earned a reputation as agricultural snake oil, which makes it hard to convince farmers to adopt the next generation of beneficial microbial technology.

Until recently, we could observe and study only microbial species that were easily culturable in the laboratory using traditional approaches, which represent a tiny fraction of the microbial world. But now we have new methods for developing microbial technology that is precisely targeted towards specific functions. We can examine microbial genes via sequencing or analyzing their function using high-throughput screening methods to find microbes with particular attributes. We also can genetically-engineer microbes to produce new strains with the characteristics we want. Or we can even synthesize entirely new species from scratch.

It’s also one thing to produce beneficial microbes that enhance plant growth in experimental greenhouses. It’s another to develop a microbial technology that can be produced at large scale, transported and stored in harsh conditions for long periods of time, and then function flawlessly in a wide range of soils and climates. For that reason, many products that are in the pipeline now still have a long way to go before they reach a farmer’s field.

Embracing our microbial world

When people think of microbes, many of them picture germs and disease. But the reality is that many microbes are beneficial, and we literally could not live without them. For too long we have ignored the benefits of a healthy microbiome in agriculture. The explosion of interest in beneficial microbes for food production is exciting and portends a future when agriculture is less reliant on chemicals. The future of food is below our feet in the invisible universe of the microbial world.

10 Best Gift Ideas for Cannabis Connoisseurs and Growing Aficionados (2022)

December 7, 2022Developing and Optimizing a Cannabis Cultivation System

December 14, 2021Dealing with Insomnia: How Can CBD Help?

December 10, 2020Your Guide to Sleep and CBD

December 7, 2020

Do you want to receive the next Grower's Spotlight as soon as it's available? Sign up below!

Resources:

Want to get in touch with person? They can be reached via the following methods:

- Website: https://mammothmicrobes.com/

- Email: info@growcentia.com

- Phone: (970) 818-3321

Do you have any questions or comments?

About the Authors

Growcentia was founded by a team of three Colorado State University PhD soil microbiologists that share a passion for enhancing soil health and promoting sustainable agriculture. Using innovative proprietary technology, this team developed an approach to identify and apply nature’s very best microbes to improve nutrient availability to plants.